Giriş

The reproduction of color in the modern industrial environment is not only an aesthetic task but also a strict engineering and cost-saving effort. With the global supply chains requiring uniformity in the various geographical markets, the printing industry has been drawn to a standardized methodological approach called process color. This system is the universal visual language that interprets digital intent into physical reality in billions of units of packaging each year.

To manufacturers and brand owners, the move towards artisanal color mixing to the systematic use of four-color process printing—and achieving a high-quality color process image—is a critical move towards scalability and predictability. This guide is a detailed analytical framework of process color, its mechanical implementation, and its extensive influence on the industrial printing industry.

What Is Process Color?

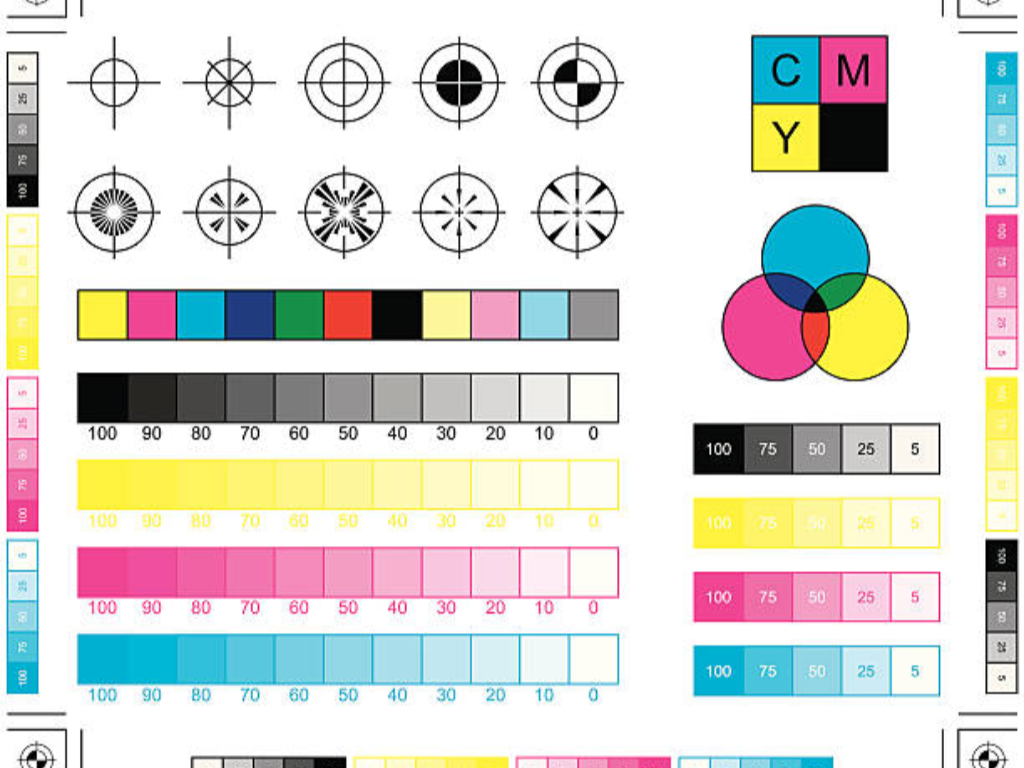

In its simplest form, process color, also known as four-color process or CMYK, is a subtractive color model in color printing. It is a system based on the chemical and optical characteristics of four ink pigments: Cyan (C), Magenta (M), Yellow (Y), and Black (K). In contrast to the additive color model (RGB) of digital displays, where light is mixed to form color, printing is a process that removes certain wavelengths of light off a white substrate. The subtractive color model is a filter that filters light by passing it through layers of ink to the eye of the viewer.

These four colors are not picked randomly but they have a basis in the physics of light. Cyan absorbs red and reflects green and blue; Magenta absorbs green and reflects red and blue; Yellow absorbs blue and reflects red and green. Theoretically, C, M, and Y should have created a perfect black. But, because of the impurities of physical pigments, the mixture usually produces a dark brown, desaturated. As a result, the “Key” color-Black is added to give density, depth, and structural sharpness, especially in text and shadow areas. This four color system is the foundation of reproducing a large part of the visible color range by a process called color separation.

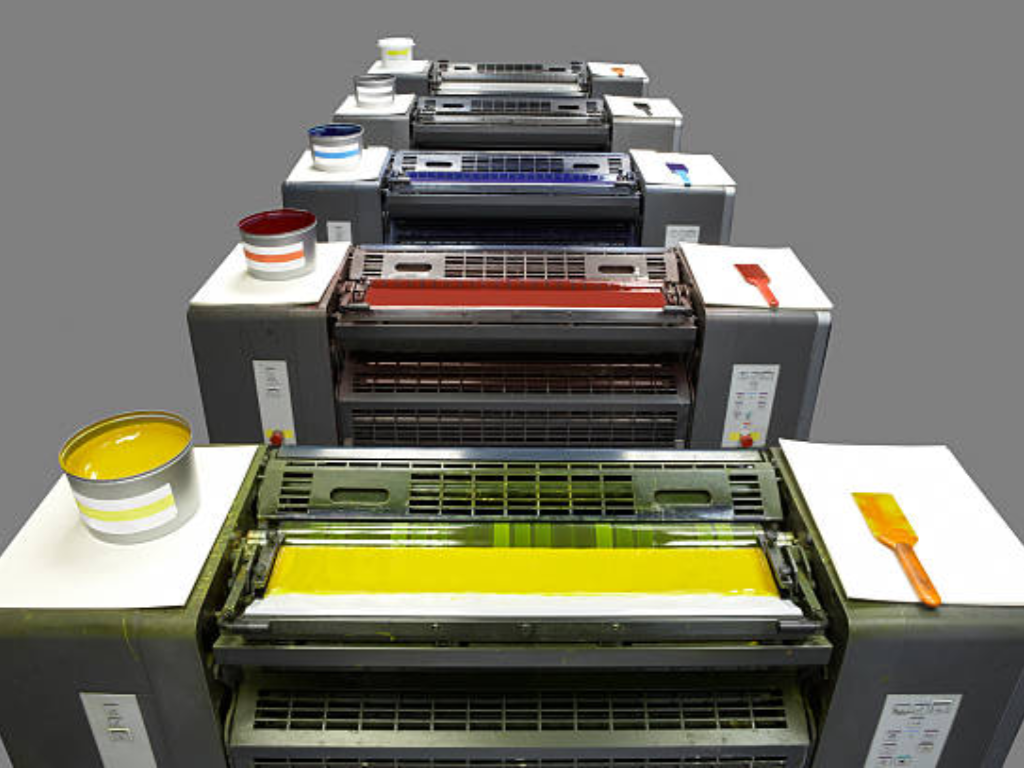

How Process Color Works: The Science of Halftone Dots

It is through the use of halftone technology that the reproduction of complex, multi-tonal images with the use of only four inks becomes possible. Since a printing press is a binary system, i.e. it can either apply ink or not, it cannot inherently vary the saturation of a single ink color over a substrate. In order to reproduce tonal variation, the image is broken down into a mosaic of accuracy called a halftone screen.

The Role of Screen Angles and Dot Overlap

The performance of process color depends on the spatial distribution of these halftone dots. When dots of specific colors and various colors were printed directly over each other or in a random manner, the effect would be a chaotic mixing of colors or the appearance of unwanted interference patterns called Moiré. To avoid this, the four color plates are allocated a particular screen angle.

Standard industrial configurations typically utilize angles such as 15° for Cyan, 75° for Magenta, 0° or 90° for Yellow, and 45° for Black. These offsets make the dots form rosettes, little circles, which the eye perceives as a continuous tone. The best way to ensure the dots overlap and are close to each other to form the final perceived color; a high concentration of Magenta and Yellow dots in a given area will be perceived as orange. The accuracy of this geometrical composition is absolute because even a few degrees of deviation can ruin the whole visual product.

Visual Perception: How the Human Eye Sees Process Color

The last phase of CMYK printing is not done on the press, but in the human brain. This is referred to as spatial partitive color mixing and takes advantage of the low resolving power of the human eye. The eye cannot see the individual halftone dots at normal viewing distances. Rather, it combines the discrete values of Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Black into one unified color.

The perception of smooth gradients, skin tones, and complex textures is possible through this psychological integration. Process color success is thus determined by the capability of the press to retain dot integrity. When a dot is blurred or enlarged, optical integration cannot occur and hue and detail loss occur. Therefore, the mechanical stability of the printing press is the most important variable in the equation of visual perception.

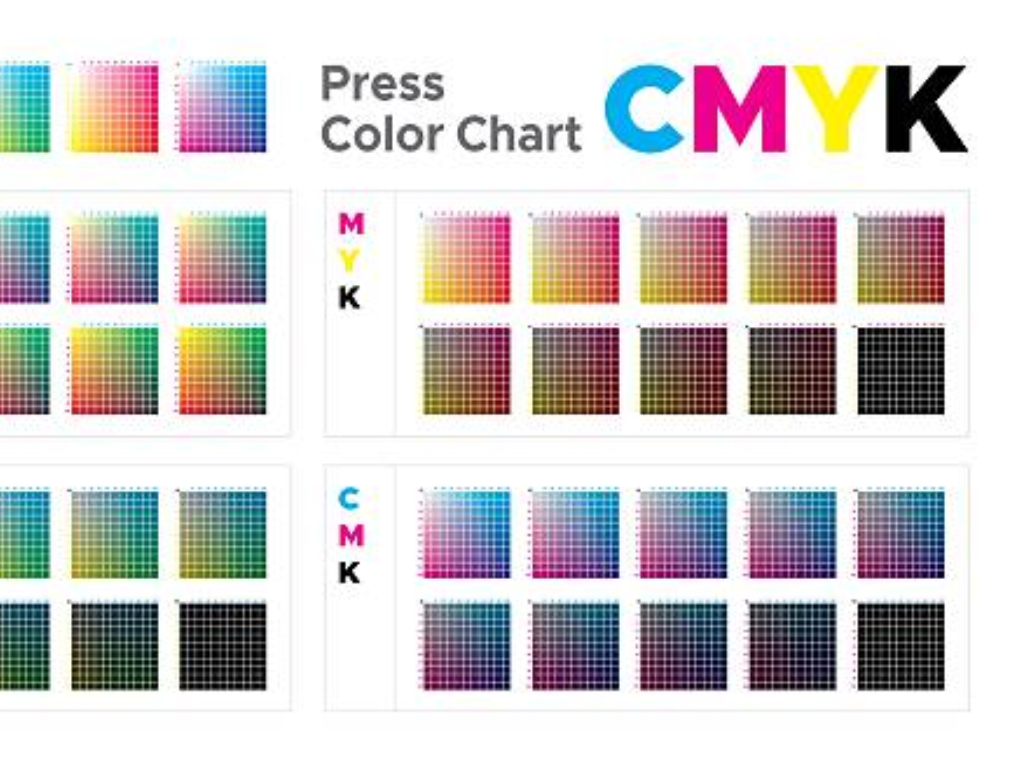

Process Color vs. Spot Color: Which One Should You Choose?

The decision between process color and spot color is a basic decision in the strategic planning of a print run, where the aesthetic needs are weighed against the financial limitations. To comprehend this option, it is necessary to compare the pre-mixed recipe of a spot color with the four-ingredient pantry of process color.

| Comparison Metric | Process Color (CMYK) | Spot Color (Pantone) |

| Color Gamut | Limited to CMYK mixing range. | Extremely wide (Fluorescents, Metallics). |

| Tutarlılık | Dependent on press stability & registration. | Absolute consistency across different batches. |

| Cost (Multi-color) | High efficiency for complex/photo images. | Higher cost (Each color requires a new station). |

| Kurulum Süresi | Faster (Standardized ink loading). | Slower (Requires custom ink mixing & washing). |

| En İyi Kullanım Alanları | Real-life photos, gradients, multi-tonal art. | Brand logos, corporate colors, solid tints. |

Precision vs. Cost-Efficiency

Spot color, which is also known as the Pantone Matching System (PMS), is the use of one, ready-to-wear ink that is designed to produce a particular hue. This provides unmatched color consistency and a broader gamut (range of colors a system can generate) than CMYK. Nevertheless, every spot color needs a separate printing station, which makes the press more complex.

Process color, on the other hand, makes use of a fixed palette of four inks to reproduce a large range of colors. It might not be able to reproduce very vivid oranges or deep purples that are available in the Pantone library, but its price-effectiveness in multi-colored or photographic work is unparalleled. The marginal cost of adding a single color to a spot color system is large, but the marginal cost of printing a new color in a process color system is essentially zero, as long as it is within the CMYK gamut.

Application Scenarios in Packaging

The nature of the design usually determines the decision. Process color is required in high-fidelity photographic reproductions, including those on food packaging. The human eye is very sensitive to the details of natural textures, and it is only possible to reproduce them with the help of thousands of tonal variations provided by CMYK.

Conversely, corporate branding and logos usually require spot colors. The identity of a brand is often associated with a particular, unchangeable color that should appear the same when printed on a corrugated box, a plastic film, or a paper label. A hybrid solution is common in most high-end packaging: “4-color process plus one,” in which CMYK color is used to print the image, and a special spot color is used to make sure that the logo of the brand is exactly the same on all platforms.

The Economic Impact: Why 4-Color Process Dominates Packaging

The logic of industrial efficiency and lean manufacturing is the reason why the four-color inkjet process is so dominant in the global packaging industry. Procurement and inventory wise, having a stock of four main inks (C, M, Y, K) is much cheaper than having a library of hundreds of specialized spot color inks. This simplification of inventory is directly translated to better cash flow and less waste since there is no chance of the specialized inks going out of date.

Moreover, process color enables standardization of press setups. The make-ready time, which is the time needed to wash ink fountains, rollers and calibrate color, is a major productivity drain in a spot-color-heavy environment. Under process color, the four main stations are loaded and calibrated. This enables quick job changes, which is a critical requirement in a world of reduced print runs and greater SKU variety. The time saved during the setup and the decrease in the amount of ink wasted make process color the most economically feasible model of high-volume packaging production.

Critical Technical Challenges in Process Color Printing

Although it is a theoretically elegant process, the mechanical and fluid-dynamic problems of process color physical implementation are fraught. The physical forces that are used in the transition of digital pixels to ink on a substrate can distort the desired outcome.

Flexo’s Battle: Managing Dot Gain

Dot gain (or Tone Value Increase, TVI) is the main problem in flexographic printing. Since flexo is a pressure-based relief printing process, the process of transferring ink through a flexible plate onto a substrate causes the halftone dots to expand. Unless the pressure is carefully regulated, a 50 percent halftone dot can grow to 70 percent on the substrate, resulting in the loss of highlight detail and a radical change in color saturation. To control this squeeze, it is necessary to have high-precision mounting and sophisticated plate-making technologies that counter the expected expansion.

Gravure’s Hurdle: Missing Dots and Cell Consistency

Rotogravure printing, though able to achieve extreme detail, has its own challenges, the most notable being missing dots or snowflaking. This is caused when the ink does not move out of the microscopic cells of the engraved cylinder onto the substrate, usually because of surface tension problems or roughness of the substrate. With process color, a single missing dot in the Cyan plate can turn a whole area of a green landscape unexpectedly yellow. The consistency of the cell and the transfer of 100 percent of the ink is important to the integrity of the process color image.

The Shared Struggle: Precise Registration for Multi-Color Alignment

Registration is the most challenging task that is common to all high-speed printing techniques. The four color plates have to be aligned to within sub-millimeter accuracy and the substrate has to move at speeds that can be in excess of 300 meters per minute to create a sharp process color image. Any deviation of a fraction of a millimeter produces a mechanical symphony of discord, which causes blurred images, color fringing (halos), and loss of text legibility. This is space synchronization, which is the final test of the engineering of a printing press.

Kete’s Solution: Achieving Perfect Process Color with High-Precision Presses

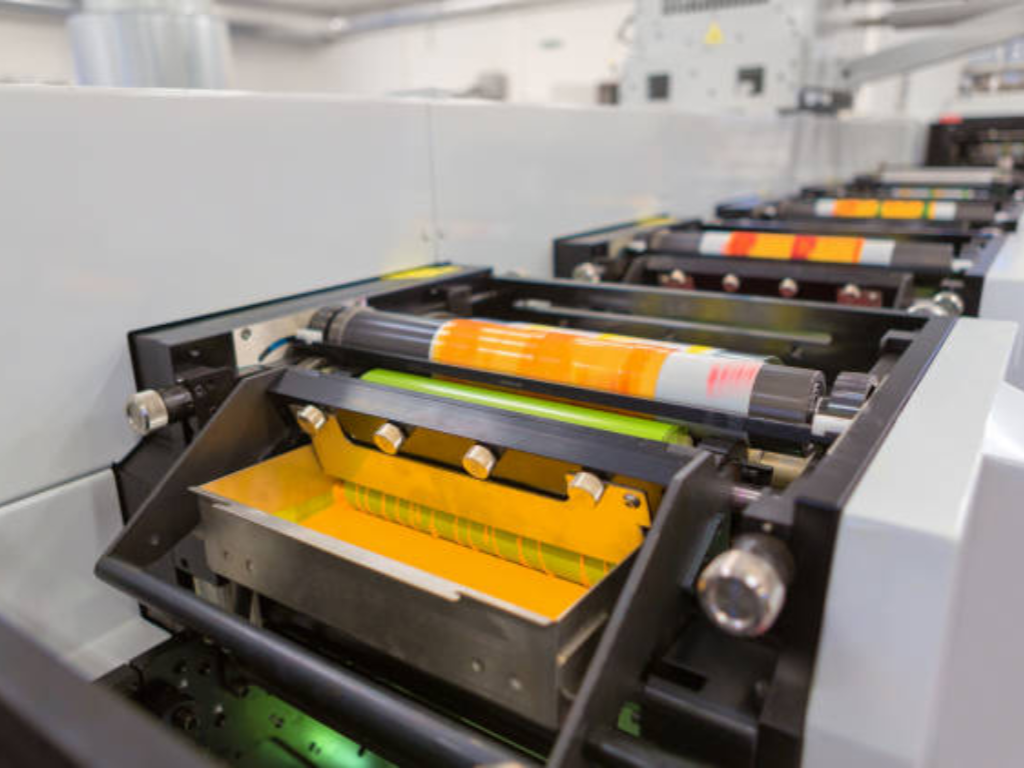

At Kete, we recognize that the theoretical benefits of process color can only be realized through superior mechanical execution. Our flexographic and rotogravure presses are engineered to address the specific “friction” inherent in process color reproduction.

For flexographic applications, Kete utilizes advanced servo-driven systems that provide unparalleled control over impression pressure, significantly mitigating the effects of dot gain. Our machines are equipped with high-performance ceramic anilox rollers, which ensure a precise and consistent volume of ink is delivered to the plate, allowing for the stable reproduction of fine halftone dots.

In our rotogravure line, we have implemented high-stability doctor blade assemblies and advanced impression rollers that eliminate the risk of missing dots, even at high speeds and on challenging substrates. Most importantly, Kete’s integrated automatic color registration systems utilize high-speed optical sensors to monitor and adjust the alignment of the CMYK plates in real-time. This closed-loop control system ensures that the mechanical symphony of the press remains in perfect harmony, delivering consistent, high-fidelity process color from the first meter to the last.

Pro Tips: Optimizing Your Workflow for Consistent Results

The operator needs to see beyond the press itself and the whole production ecosystem in order to get professional-grade process color. The accuracy of a four-color reproduction is a fine balance between chemistry, physics and mechanical stability.

Substrate Influence on Color Accuracy

The optical behavior of the process color dots is determined by the physical properties of the carrier material, be it polymer-based or cellulose-derived. A one-size-fits-all attitude to ink density in industrial packaging results in disastrous color changes.

The adhesion of ink and light reflections on different substrates such as BOPP, PE, and PET pose different challenges. As an example, PET offers a high-clarity surface that allows color vibrancy to be more vivid, whereas PE, because of its natural elasticity, needs a high level of tension control to avoid registration drifts during the CMYK layering process. Paper and board, on the other hand are porous; the ink soaks into the fibers and can artificially darken the process color by over dot gain. The key to mastering color is to master the substrate.

Critical Workflow Adjustments

Substrate Pre-Treatment: Ensure that your substrate has the correct surface tension. For plastic films, corona treatment is essential to ensure that the process color dots adhere and do not spread uncontrollably.

Viskozite Kontrol: The “tack” and viscosity of C, M, Y, and K inks must be balanced. If the Magenta ink is significantly thinner than the Cyan, the sequence of ink trapping will be compromised, leading to unpredictable color shifts.

Environmental Stability: Temperature and humidity can alter both ink chemistry and substrate dimensions. Maintaining a climate-controlled pressroom is not a luxury but a requirement for high-precision process color work.

Regular Calibration: Use spectrophotometers to monitor the L*a*b* values of your process colors during the run. Do not rely on the naked eye; rely on data to ensure that your CMYK output remains within the target tolerance.

Sonuç

Process color remains the cornerstone of the modern printing industry, offering a sophisticated balance of visual versatility and economic scalability. By understanding the underlying physics of the CMYK model and the mechanical rigors of halftone reproduction, manufacturers can navigate the complexities of global packaging demands. While the challenges of dot gain, registration, and substrate interaction are significant, they are not insurmountable. Through the application of high-precision engineering and rigorous workflow optimization—principles that define the Kete approach—the potential of process color is fully unlocked, ensuring that every printed image is a testament to industrial excellence and technical mastery.